Intro

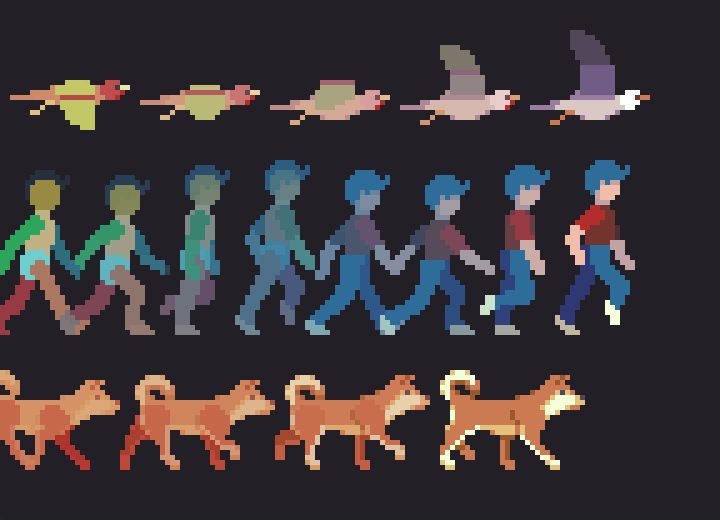

Everyone and everything gets around in their own way; some on two, some on four, and some like to soar. In this lesson I present motion studies on 3 different subjects that are essential to hang on any animator’s tool belt. First, we’ll take a look at bipedal locomotion with a human walk cycle, then we step it up to four leg action with a dog walk cycle, and finally take to the skies with a study on the wing motion of birds.

Human Walk

A human walk cycle is always a good place to start your animation studies, or to polish your skills. In my opinion, the subtle movements of a walk make it a bit harder to animate than a run cycle. I cover run cycles in Pixelblog 8.

I present a standard walk cycle here with some exaggeration to help illustrate the subtle mechanics of the motion. Start by making a figure with the body parts clearly defined by color. It’s much easier if you animate one section at a time for all frames. Animate the legs first, then the arms, head, and overall body movement. Take careful note of the position of all the body parts in every frame.

Once the animation is satisfactory you can color and add details. The more detailed the design, the more difficult it will be to keep the movement clean. I recommend keeping your characters simple, especially if you are new to frame animation.

This is a standard walk cycle, but the motion can vary greatly depending on body type, age, and circumstances. To introduce more personality, observe real people and try incorporating their unique movements into the animation. For example, a carefree child marches with pride, the elderly shuffle slowly with hunched backs, the drunk sway and stumble, and so on.

Dog Walk

Quadrupeds are animals that walk on 4 legs. While they exhibit some of the same mechanics seen in bipedal locomotion, the additional set of legs further complicates things. You should have a firm grasp of 2 legged walk cycles before attempting to animate a 4 legged walk.

I chose Shiba Inu, to illustrate quadrupedal locomotion. I’ve never owned one, but surely they’re the cutest!

Same as the human, break the anatomy down into separate body parts defined by flat colors. Think of the legs as 2 sets of biped legs. The bone structure is different than a human but the principle stepping motion is very similar. Animate one set of legs at a time, then do the body, head, and tail.

Observe how the back leg follows one step behind the front leg of the opposite side. Make sure the distance traveled is the same for both the front and back legs, or the body will appear to stretch and contract like an accordion.

Pay close attention to every body part in every frame and make sure the energy of the motion is consistent throughout. The up down motion of the back pelvis and front shoulders undulate with opposite but equal motion, creating a balanced rhythm across the back.

When dogs and other quadrupeds begin to run they actually bound, with the right and left legs working more in parallel. I’ve done one personal study of a bounding dog before and hope to cover it in a later lesson.

Bird Flight

Now you’re probably tired of all those legs, so let’s lighten things up and take to the sky with some simple wing motion.

I modeled this example after medium sized sea birds, which can provide a template for many bird species and winged creatures.

As with the previous studies, establish the motion with simple shapes made of flat colors. From the front view my wings are simply a wireframe. Make sure to mark the joint placement on the wings. This helps prevent the wings from looking too rubbery by providing a clear folding point.

I went with 8 frames to stay consistent with the other studies and to clearly describe the full arch of motion, however, I think a convincing wing motion can be done with a few less frames. The extremes of motion are keyframes. so you should start with these. then do the smear and take it from there.

Start with the front view before attempting the side view. Animate only the wings first, then add the overall bobbing motion last.

Once the motion is satisfactory, you can color and add details. Notice how I thickened up parts of the wings and added visible tail feathers in my finished version of the front view.

FINAL THOUGHTS

I use a fairly realistic style with some degree of exaggeration for these studies in order to best illustrate the basics of the motion. If I were making sprites for a game I would go for more stylized designs with personality, and possibly with less frames.

In order to develop animation skills one must learn to keenly observe the world around them and the manner in which all things move. However, without tangible practice it’s hard to make those senses kick on. Once you actually go through the exercises you’ll suddenly start noticing all kinds of little nuances of movement in real life. But it won’t stick if you don’t keep practicing. Animation requires a lot of repetitive practice on a regular basis. At least it does for me. So I’ll try my best to keep on practicing and sharing the fruits of my studies with you. Much more to learn!

RESOURCES

Was this article helpful? If you find value in my content please consider becoming a Patron. Among many other rewards, Pixel Insider members get extra resources to compliment my tutorials. But most importantly, you allow me to continue making new content.

Assets featured in this Pixelblog are available in Anatomy & Animation Asset Pack.

Source file used in the making of this Pixelblog is available in Tutorial 63 Source File

All contents of this lesson use my custom palette Mondo

Get caught up on all my downloads

If you're not ready to commit to the subscription model of Patreon, make a one-time donation and receive exclusive art and resources. Help continue the content by providing me a living. Thank you!